Chapter Two

Ich bin ein Berliner!

We all breathe the same air, we all cherish our children’s future, and we are all mortal.

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (1917-1963).

35th President of the United States.

Chapter Highlights

Just months before he was assassinated in November of the same year, President John F. Kennedy gave an emotive nine-minute ‘city hall’ oration in West Berlin on June 26th 1963 to a 150,000 person crowd mustered in the square outside Rathaus Schöneberg where it was presented. It was beamed to a global television audience of hundreds of millions and harboured a strong message to his Soviet adversary, Nikita Khrushchev, at the height of the Cold War.

The speech echoed with twin themes of freedom and peace, and Kennedy concluded with the famous statement that:

All free men, wherever they may live, are citizens of Berlin. And therefore, as a free man, I take pride in the words ‘Ich bin ein Berliner!’

This simple German phrase (I am a Berliner) was used twice in what was J.F. Kennedy’s most-watched/listened-to speech in ‘real-time’, of all time.

To put this in perspective, here’s a hypothetical: in 1945, an aspiring PhD student proposes to undertake a comparative analysis of two economic systems – command versus free-market – involving approximatively 600m (human) subjects split evenly between two geographically proximate political systems – communism versus liberal democracy – in a European context raw with fresh wounds gouged by eugenics and pogroms.

Throw in a few hypotheses, observe for 45 years and note what occurs. It is an absurd proposition, but this is what happened between 1945 and 1991 on the continent of Europe.

Winston Churchill, the man who said he knew what would be in the history books because he planned to pen them, had seen the writing on the wall. In his Sinews of Peace speech given at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri on March 5th 1946, Churchill was the bearer of stark news to his captivated audience:

It is my duty to place before you certain facts about the present position in Europe. From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic an iron curtain has descended across the Continent. Behind that line lie all the capitals of the ancient states of Central and Eastern Europe. Warsaw, Berlin, Prague, Vienna, Budapest, Belgrade, Bucharest and Sofia, all these famous cities and the populations around them lie in what I must call the Soviet sphere, and all are subject in one form or another, not only to Soviet influence but to a very high and, in some cases, increasing measure of control from Moscow.

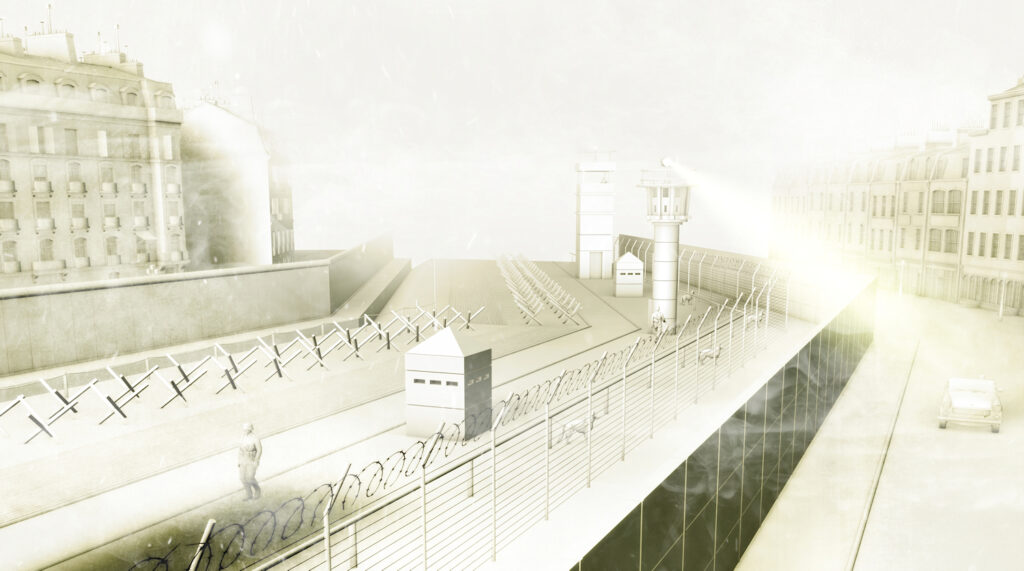

Reverting to Kennedy, the ‘writing on the wall’ was most visibly centred in and coiled around Berlin and, from the vantage point of his podium when making his speech, he could see its ugly legacy, adding:

Freedom has many difficulties, and democracy is not perfect, but we have never had to put a wall up to keep our people in, to prevent them from leaving us.

Twenty-four years later – June 12th 1987 – the uber anti-communist US president Ronald Reagan, speaking in front of the Brandenburg Gate and standing alongside the Berlin Wall, laid down the following challenge to his new Soviet geopolitical sparring partner, General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev:

if you seek peace, if you seek prosperity for the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, if you seek liberalization, come here to this gate. Mr Gorbachev open this gate. Mr Gorbachev, tear down this wall!

Reagan’s bravado was bolstered by an unlikely positive outcome of an earlier meeting in Reykjavik, the Iceland capital, on October 11th – 12th 1986. Described as ‘the doomed summit that ended the Cold War’, the legacy of this ‘soft summit’ fed into geopolitical realms beyond its stated goals relating to nuclear disarmament and arms control.

While Kennedy’s speech was delivered at the vertex of the Cold War, Reagan’s marked the dawn of its nadir. Within two years of President Ronald Reagan delivering this impassioned speech, the Iron Curtain was breached: not in Berlin, but in Hungary; and not through iron or concrete, but via an open wooden door.

Please click/tap your browser ‘Back’ button to return to the location navigated from. Alternatively, click/tap the ‘The Long March of Globalization’ graphic below to navigate to the Ten Years… The Book page.

All content © Colin Edward Egan, 2022